An eventful history

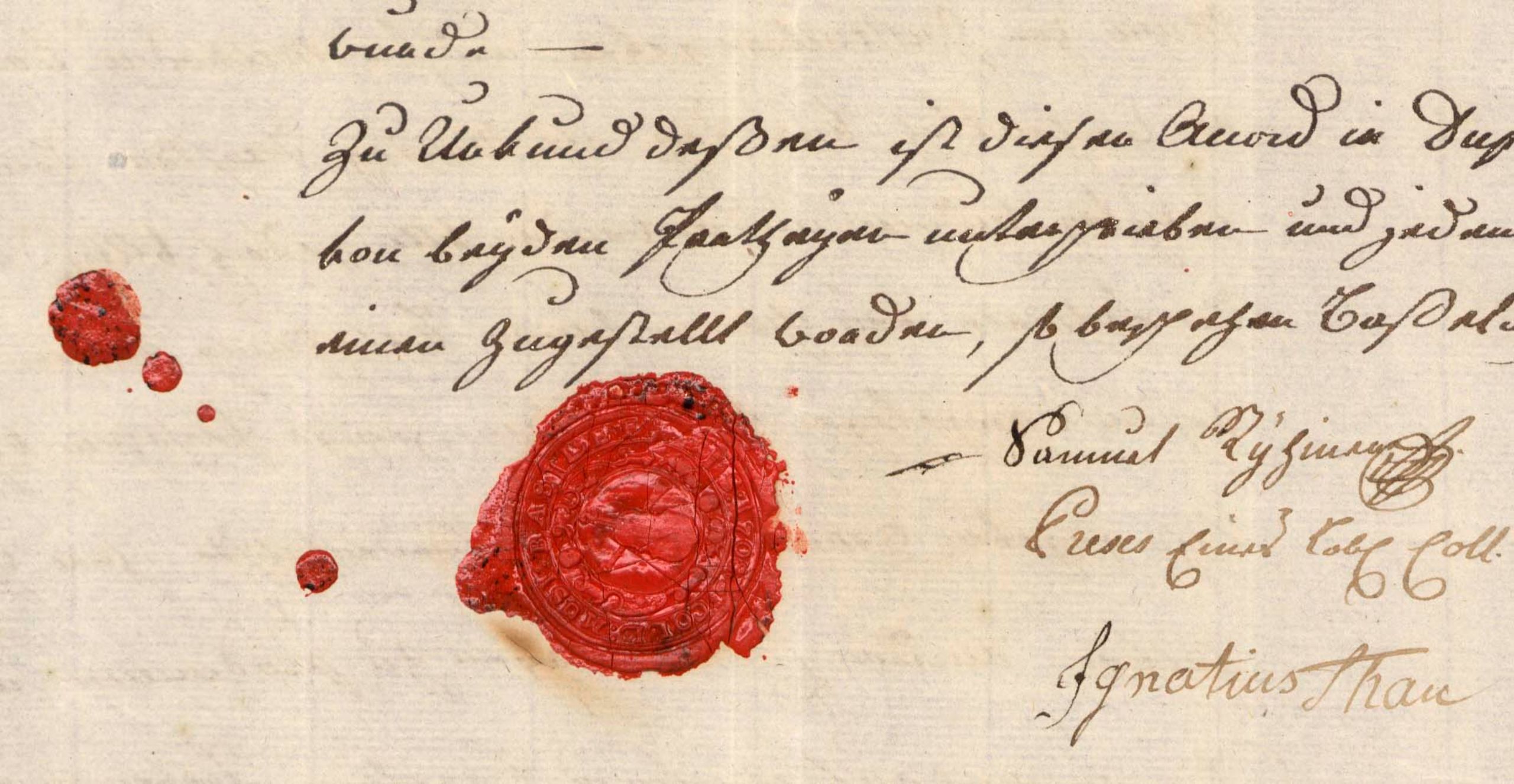

The Sinfonieorchester Basel came into existence when the Basler Sinfonie-Orchester merged with the Radio-Sinfonieorchester Basel in 1997. But that's only part of the story. The present-day Sinfonieorchester is the heir to a tradition that goes back more than 300 years. It is a story rich in highs and lows. Larger-than-life personalities and artistic ambitions play their part, and so do institutions, concert halls and money. The name of the orchestra has been changed several times, and more than one sponsor has had to abandon it because of financial problems. But apart from the brief period of the Helvetic Republic, the ensemble itself never disappeared from the scene.

Compiled by Simon Niederhauser

Sources

_bearbeitet-1.jpg/jcr:content/1826_Stadtcasino.jpg)